Last month I sent a few friends a professional headshot of myself and asked what they thought. I received several ecstatic reviews.

“Finally, a professional photo that fits a co-founder.”

“What a nice smile :)”

What they didn’t know was that the photo I had shared was actually, 100% AI-generated. I had never donned a gray blazer or stood in front of the backdrop.

After learning my little secret, the tone shifted. Every single friend backtracked with some serious scrutiny. An insistence that they had actually suspected, all along, that the image wasn’t real.

“The hair was a bit too smooth. I just figured it was retouched.”

“I knew the smile was weird somehow …”

“It’s just so not your style. White t-shirt? Silver dangle earrings? Please.”

The responses hinted at something deeper than just the photo. For years, researchers have attempted to make realistic, AI-generated photos. So why does it feel so unsettling when an AI finally dares to succeed? As someone who is involved in the broader AI space, I was curious to dig into this feeling. So I set out to get my hands dirty and do some research of my own. A personal, weekend project was born.

Behind the AI boom: Pure Vanity

My journey into AI image generation started on LinkedIn. For 10 years, I had managed to get by using the same profile photo. Now as I headed into a more mature era of my career, I was overdue for an update. But getting a good headshot was a losing battle. Working in tech, I had never needed to invest in quality business apparel, and the Boston humidity demolished the little control I had left to exert over my hair. So to make myself look presentable, I ventured into the AI world. As it turned out, AI had my back.

Vanity, it seemed, was a key motivator behind an entire marketplace of AI photo apps. I was overwhelmed. Some like Lensa AI offered stylized presets, promising to turn me into an ancient pharaoh, cyberpunk adventurer, or mythological creature. Others like AI Headshot Generator were focused on realism, placing me in cityscapes and office spaces. I view this genre of vanity as an equalizing force. In a world where we are constantly, subconsciously judged by our appearance, why not use extra tools to put our best foot forward?

The idea is as enticing as it is timeless. Doctored portraits from the 15th century are not too different from millennials touching up their selfies with FaceTune. Today’s AI, though, has significant improvements. For one, you can actually converse with the AI in plain English. And then, the possibilities are virtually limitless. As long as you can describe your idea, the AI can supposedly generate an image to illustrate it. Or at least, that’s what I wanted to test.

Using AI to capture my own likeness

When using a text-to-image AI, you input a description and the AI model provides an image that matches it. The AI has been trained on millions of examples, allowed to learn the correlations between a caption and its corresponding image. Interesting patterns emerge over time. For example, the model learns to associate specific groups of pixels with concepts such as “woman” or “digital art.”

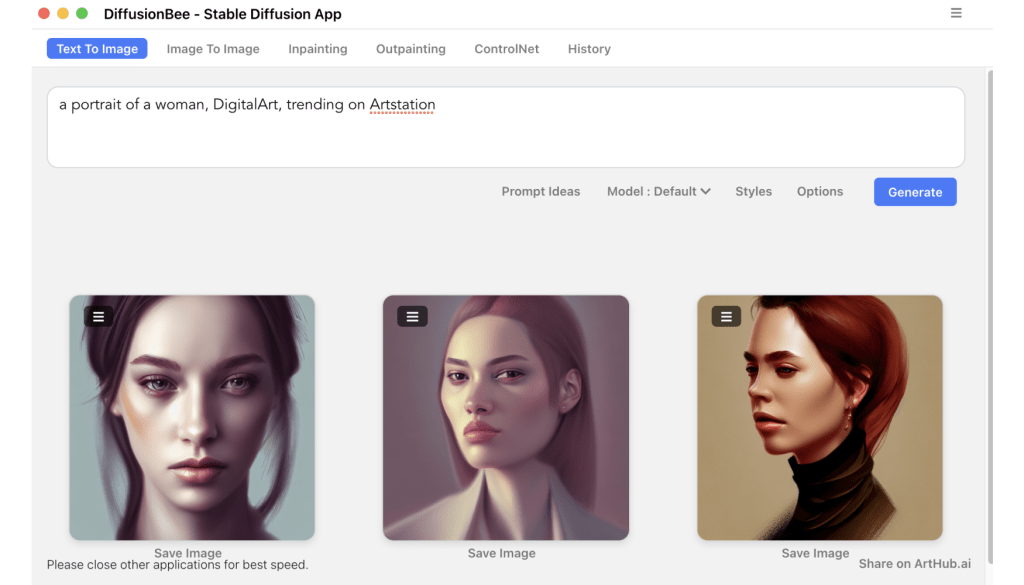

I tested this with Stable Diffusion, an open source AI model that is available for free. Better yet, the DiffusionBee software allowed me to install and access Stable Diffusion easily. Then all I had to do was type my description, such as “a portrait of a woman, DigitalArt,” and click to generate images.

The only catch was that I couldn’t make an image of myself. Stable Diffusion didn’t know who I was, because the original learning examples came from publicly available data. I was never mentioned.

To capture my likeness, I had to continue training the model myself, using a few of my own selfies. The basic idea is to take a concept the model already knows, such as “woman,” and teach it to understand more nuance, such as “a woman named Neha Patki.” (This technique, called DreamBooth, is accessible through a number of tutorials.) After training it with 10 selfies for 20 minutes, there was a new variant of the model. I had essentially made a private copy of the AI, one that knew who I was. It was capable of creating images that looked like me. I could even combine the prompt “Neha Patki” with the other concepts it knew, producing my likeness in a variety of settings and styles.

I had essentially made a private copy of the AI, one that knew who I was.

Most AI photo apps work the same way, but they don’t provide raw, unfiltered access to your personal AI model like I had. The process had captured my face through complex, mathematical formulas. Through playing around its outputs, I could see the obvious parallels to the cues an artist would use: skin, hair, and eye color, detailed proportions of the face, and idiosyncratic expressions. Admittedly, this took the magic out of recognizing myself. My entire likeness was suddenly sitting in a 2GB file on my computer.

Beyond the uncanny valley: Our collective discomfort with AI portraits

I wish I could say that understanding the model made me completely comfortable with the concept of AI-generated portraits. But there is still something disarming about recognizing myself in a photo that I’ve never taken, in clothes I’ve never owned, or in a city I’ve never visited. It’s as if I suddenly have a twin who is masquerading as me.

Then again, I’m partial to the obviously stylized portraits the AI model creates. I find these avatars absolutely adorable. They bear less resemblance to me, but I can easily envision a VR environment where I would happily play the character. Perhaps these are comforting precisely because they are stand-ins. They never promised to replace my actual identity, so they pose no threat to my personhood.

On the other hand, when I requested more realism from my AI model, it occasionally produced something nightmarish. My features were warped out of proportion. I had a murderous grin. I’d suddenly sprouted a third arm. A clear failure to accomplish the task.

This phenomenon is called the uncanny valley, wherein an AI attempts to improve realism but falls short of its goal. The result is straight out of a horror movie. But I posit that there is still something comforting about these creepy bloopers. A tacit admission that AI is not that powerful yet.

If we were still in the uncanny valley, I would not be writing this article. To the best of my estimates, about 10% of my photos now pass the Turing test. This means most people (including my own mother) cannot tell a real photo apart from an AI-generated one. And that can feel like a personal attack. I had never considered my likeness to be sacrosanct but perhaps unknowingly, I had assumed only cameras and great artists would be able to capture me well. An AI being able to replicate my face is like an AI peering into my soul. Absolutely verboten.

About 10% of my photos now pass the Turing test … and that can feel like a personal attack.

This doesn’t even begin to cover the issues with control or legal ownership. There is growing discomfort in AI’s unrealized potential. A number of celebrities are actively fighting lawsuits over the ownership of their likeness. Fictional works are pushing that exploration further. Black Mirror’s “Joan is Awful” is a story about a woman who unwittingly signs away the rights to her likeness to a streaming service. And given that I’m currently in possession of a digital file containing my own likeness, this already feels too close to home.

The curse of AI

However we feel about it, AI is already living among us. Some AIs are silently powerful, like how your last credit card purchase probably cleared through a fraud detection algorithm. Others are loud. In 2018, an AI-generated influencer appeared on Time Magazine’s list of the top 25 most influential people on the internet. With close to 3 million followers, she has brand deals, fights with her siblings, and releases her own music (it’s not bad). When an AI becomes so widely adopted and adored, we stop thinking of it as AI — almost as if we want the word “AI” to live on mythologically as a looming threat. This is the curse of AI.

In a small but growing corner of the internet, AI enthusiasts continue their work amidst the discourse. They are training models and creating a community to build on each other’s work. As of this moment, there are over 6,000 variants of Stable Diffusion. Some are optimized to make images more aesthetic, while others promise to create cartoon monster QR codes. There’s a beautiful chaos about it that reminds me of the internet circa 2005. Of course we still have many decisions to make about the acceptable use of AI images. The only thing we cannot feasibly do is take back the technology.

“So what comes next?” a friend asks as I show off my latest AI model.

“Maybe we won’t need to take as many photos anymore,” I posit, “just let the AI handle things.”

“We could stop worrying about capturing everything all the time,” he adds, “put our phones away — breathe.”

Header image credit: Brett Sayles on Pexels

Leave a comment